Tallgrass Prairie – A Bird’s Eye View

The tallgrass prairie once covered 170 million acres, and at the 2023 North American Prairie Conference, I was reminded of that continental scale. Between assisting presenters with technology, I heard sessions about protecting orchids in the aspen-prairie parkland of Manitoba, time lapse photography along the Platte River in Nebraska, beetles in the prairies of Alabama’s “Black Belt”, restoring spring wildflowers on the Kankakee Sands of Indiana, and building out the native seed supply chain in South Dakota, as well as lots of good information from friends and colleagues in Iowa. The following are a few insights I picked up from the conference, written from a bird’s perspective.

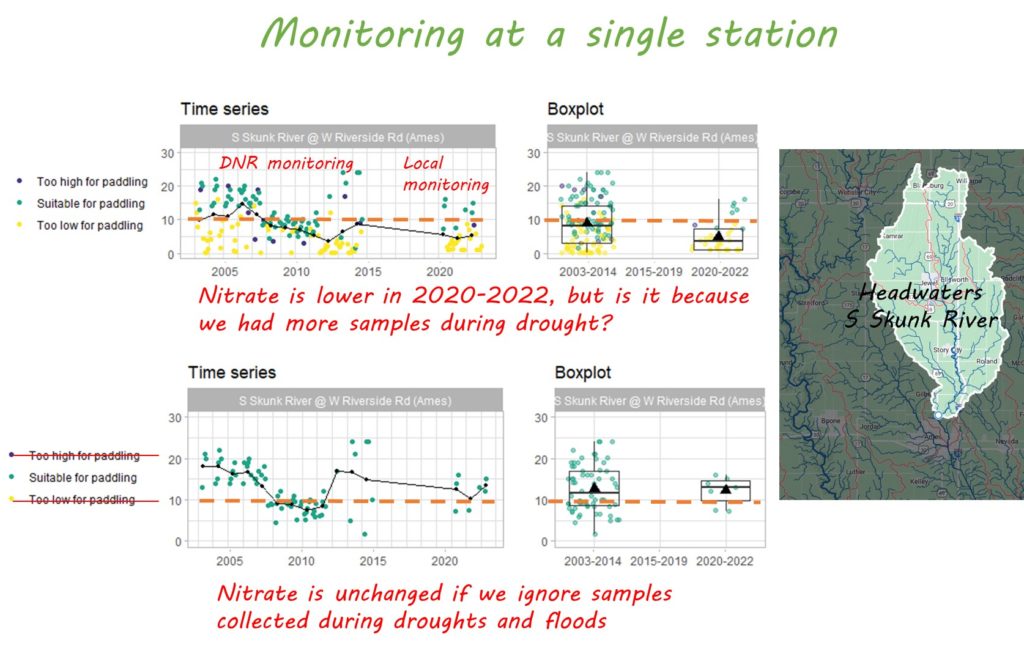

Hi, I’m an eastern meadowlark (Sturnella magna). I grew up in the tallgrass prairie, but I’m not picky about the species composition of my grassland habitat. I was the most common bird in Iowa for a century after the prairie sod was broken, making a good living in hayfields and hedgerows. Things didn’t get really bad for me until the second half of the twentieth century, when most Iowa farms dropped alfalfa, hay and small grains in favor of corn and soybean production at ever larger scales. That conversion is also the root of the nitrate problems in Iowa’s rivers.

But the flip side of that is that grassland generalists like me don’t need a perfectly authentic prairie to make a comeback. A food system that included more pasture and forage crops to raise animals could make a big difference for wildlife, water, and the vitality of rural communities.

For more on this concept, see the University of Wisconsin’s “Grassland 2.0” project, which is reimagining a food system that provides the ecological functions of prairie. The new book “Tending Iowa’s Land” edited by Connie Mutel comes to the same conclusion: the book introduces Iowa’s four worst environmental crises with a combination of science and stories, explains their historical roots, and outlining visions for a more sustainable future. Laura Jackson’s presentation also provided inspiration for this article.