The Good, the Bad, and the Alternatives to No Mow May

If you’re involved in any kind of pollinator or wildlife hobbies, you’ve probably heard of “No Mow May”. An initiative that started in the United Kingdom, No Mow May is a campaign aiming to encourage people to stop mowing their lawns during the month of May to help pollinators. The idea is that leaving your mower parked for a month in spring will allow dandelions and other lawn-associated flowers to grow, providing food for emerging pollinators at a time when there aren’t many flowers blooming yet. This sounds easy and beneficial, but is it really? Are there better options, or is this the answer to pollinator-friendly yarding? Let’s mow through the jargon, discuss different viewpoints, and offer simple alternatives.

There are many positive and negative opinions surrounding the No Mow May campaign.

Let’s start with the positives:

- No Mow May is a catchy slogan.

- It allows dandelions, clover, violets, and other flowers to bloom.

- Generalist bees, such as honey bees, may have more food options.

- It keeps neighborhoods more peaceful.

- You save money on gas, and maybe on fertilizers/pesticides as well.

- 31 days of no fertilizers or pesticides is good for the environment (and water quality!).

- Ground-nesting bees may be disturbed less.

- You’re contradicting the status quo about what yards “should” look like.

Now for some cons to consider about No Mow May:

- It’s only for 31 days. Pollinators are active at least from April to October (which is 184 days).

- Only honey bees and other generalist bees can benefit.

- You may spread invasive species such as dandelions and dutch white clover.

- Dandelion and clover provide sub-par nutrition compared to native flowers.

- Weeds can perpetuate the image that eco-friendly lawns are just careless and messy.

- It may upset your more traditional neighbors.

- Some may use more herbicides after No Mow May to get their lawn “back to normal”.

- Cutting a large amount of grass length in one go can stress the lawn, if you keep it.

Many articles will discuss these different viewpoints, but few tell you exactly how to start a pollinator garden. Or they do tell you, but it’s pretty heavy reading, or tells you to start in fall. This article is for those needing simple steps and instant gratification. While yes, in most cases it is best to start in the fall (for seeding), if you’re willing to buy potted plants and plugs you can get outside now, while you’re excited to, and have some happy pollinator plants this summer. We’ll start with steps to selecting plants and container gardening, and then dive into in-ground gardens.

Start easy with container gardening

The easiest thing you can do is to buy a potted plant and stick it on your porch or patio. You probably do this already – why not choose one that will make both you and pollinators happy? To start considering which plants to bring home, first ask if the store or nursery has any certified USDA organic plants; if they do, these plants are less likely to make pollinators sick as they will have little to no harmful chemicals. Next ask if they have any native plants.

The art of observation

Once you are in the organic and native section (or sadly, in a random flowering section because there are no such plants available), the key to narrowing down the plants you should get is observation. Walk slowly through your plant options and watch the plants to see which ones are visited by pollinators. Those are the plants you want to look at. You may notice that nothing ever visits a pansy or petunia, but sunflowers or tube-shaped flowers are all a-buzz. While it is best to buy native plants, some plants such as irises and sedum will attract pollinators even though they are in a pot, and you can easily find them at local nurseries and big box stores (keep nonnatives in a pot to keep them from spreading).

Cultivars and creepers aren’t keepers

Be mindful of plants labeled as “double bloom” or ones that have fancy names, even if they look like a native plant. These are likely cultivars, and pollinators won’t visit them very much, as those extra-big flowers normally don’t have any pollen or nectar. If they do have some sort of food, pollinators have a hard time pushing through those extra petals to get to it. Try to stay away from anything that has the word “creeping” or “spreading” in its name, and check the label to see if it’s “aggressive” or needs a large area for its “spread”. This will keep you from bringing an invasive plant home that could escape your patio. Do keep in mind, however, that it’s going to be a lot more fun for you if you buy native plants, as they will likely attract many more pollinators! Lastly, try to choose at least three flowers – one that is currently in bloom, one that will bloom in summer, and one that will bloom in early fall. This will ensure you are supporting pollinators throughout the year, and also allows you to enjoy flowers during the entire growing season.

Pots are easy; finding native plants isn’t

It isn’t as easy to find potted native plants as it is nonnative plants, but it’s better than it used to be! Semi-local native seed companies such as Allendan Seed Co. and some local nurseries may sell native plugs during the growing season. You can also scope out Facebook for local native plant swaps. When buying or swapping plants, ask them if they are likely to bloom this year or the next; some perennial plants take two years to bloom, even if you buy a plug and not seed; it’s good to set your expectations. Also ask where the person got the seed to grow the plant, or if it’s been treated with chemicals recently. If they can’t answer these questions, find a polite way to exit. In terms of native plants that grow well in a pot, beardtongue is an earlier bloomer, and bee balm as well as black-eyed Susan are great plants that will bloom later on.

Bumble bees love beardtongue flowers.

Borders are an easy space to add pollinator habitat.

Gardens attract and support the most pollinators

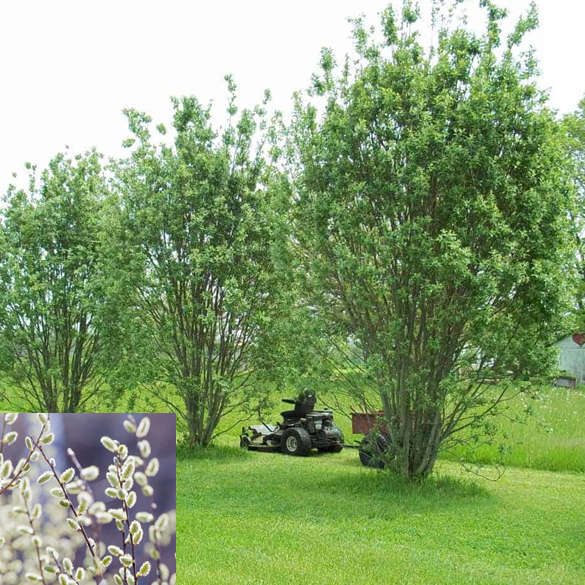

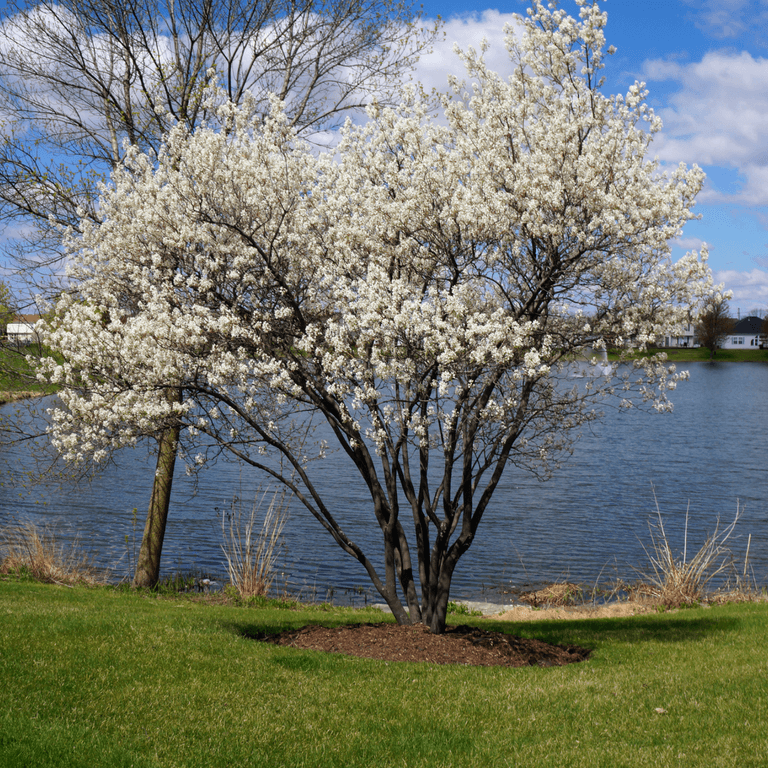

Carving out a piece of your lawn to create a garden is the best thing in the world that you can do for pollinators. Start a small, manageable garden this year with some plugs from a reputable plant supplier (Allendan, Iowa Native Trees and Shrubs, Blooming Prairie Nursery, Prairie Moon Nursery) for instant gratification. You can create a small garden on the side of your house that’s annoying to mow. Or maybe there’s an awkward corner in the back of your yard that the kids don’t really play in. Those areas are great places to start.

Natives are a must

Choosing plants for a garden follows the same rules mentioned above for container gardening, except it is much more important to have native plants that were grown relatively local. Putting a plant of dubious quality in the ground lowers the chance it will survive and flower for you later. Or worse, planting a nonnative plant in the ground could lead to it doing too well and spreading across your yard, forcing you to hack away at it all next year (remember those lilies of the valley your friend can’t get rid of? You don’t want that).

Replace the grass

To start planting your native plugs, you’ll have to kill the grass. A good tilling deep into the turf is a quick way to get started. A few rounds of glyphosate or roundup will also do the trick, but that’s a pretty nasty chemical. Covering the area with cardboard and compost on top for a year is a great way, but it’s obviously a better method for a fall planting rather than an immediate one. After you’ve removed the grass, plant your plugs. Grouping the same flower species together will attract more pollinators and make the garden look more intentional. Choosing different flowers that have different shapes and colors will attract and support a higher diversity of pollinators. After planting, water your new garden well for the next few weeks! Leaving some bare dirt may encourage native bee nesting; however if you’d like to mulch, use natural, undyed and untreated wood chips and leaves to keep turf grass and weeds at bay. Adding a natural wood border or rocks can add more nesting habitat. Lastly, be sure not to fertilize or use pesticides on or near your pollinator garden. Fertilizer will only encourage weeds, and pesticides will harm any pollinators that visit.

Tilling is an easy way to remove grass.

Enjoy your handiwork!

Creating a pollinator garden is infinitely more rewarding than merely pausing the mower during May. By adding native plants to your yard, you will not only start seeing bees, but possibly new kinds of birds, butterflies, fireflies, and other wildlife. You’ll be able to enjoy your handiwork for not one month, not two, but years to come.