A Novel Way to Preserve a Historic Dining Experience

Lizzie’s Dining Car & Caboose Bar is a new dining experience based upon the historic passenger cars that frequented Marengo from 1860-1970. Located at 1041 Court Ave, Marengo, Iowa, the immersive experience Elizabeth Colony has created is that which can be compared to a movie set created in Hollywood. The transformation of blank walls in a brick and mortar building into a trip back in time on a railroad dining car is enhanced with “windows’ ‘ showing outdoor scenes that move at the speed of a locomotive. Only the smells and tastes of the home cooked food and drink give away the truth that this is not an actual passenger dining train.

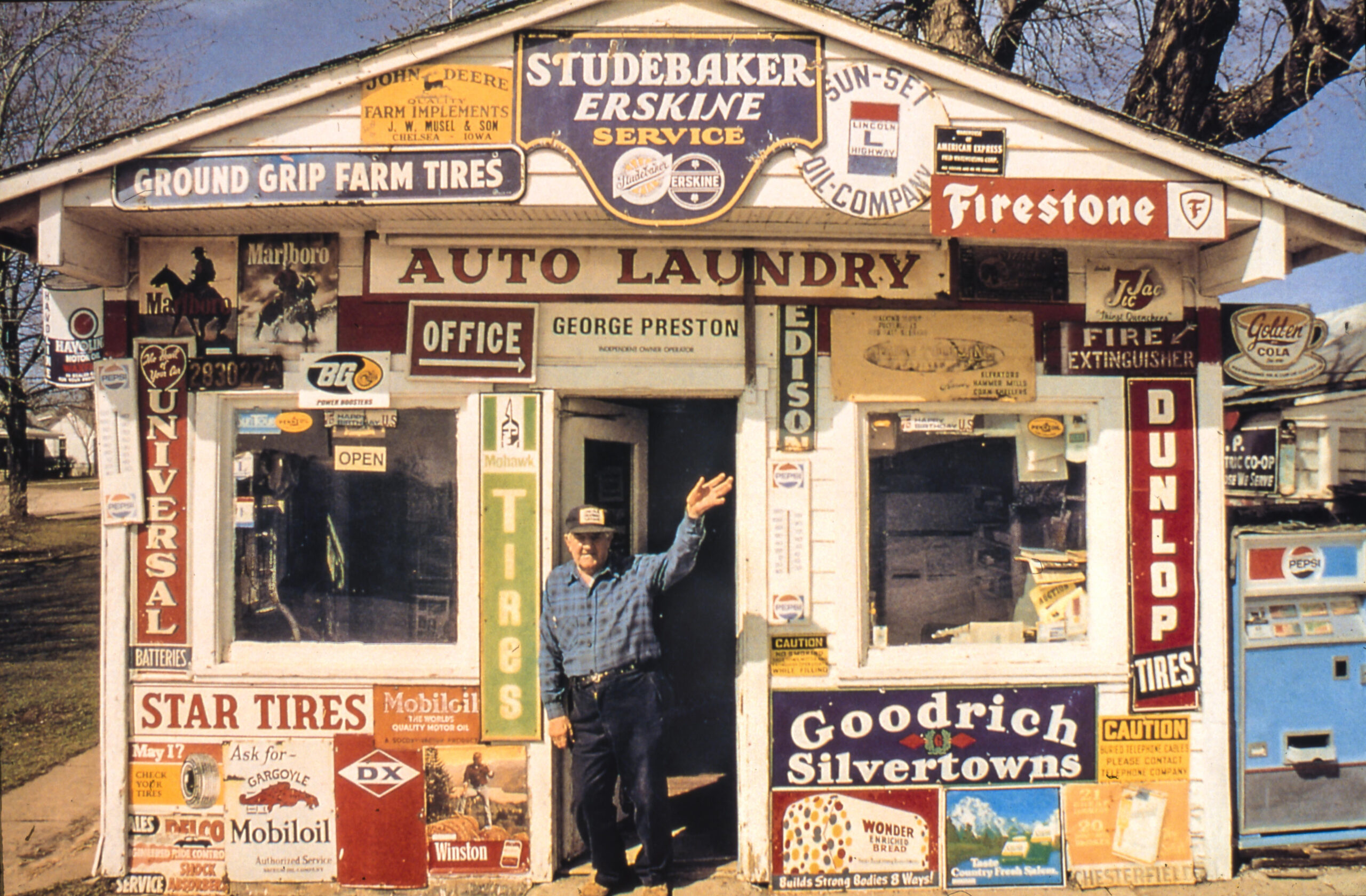

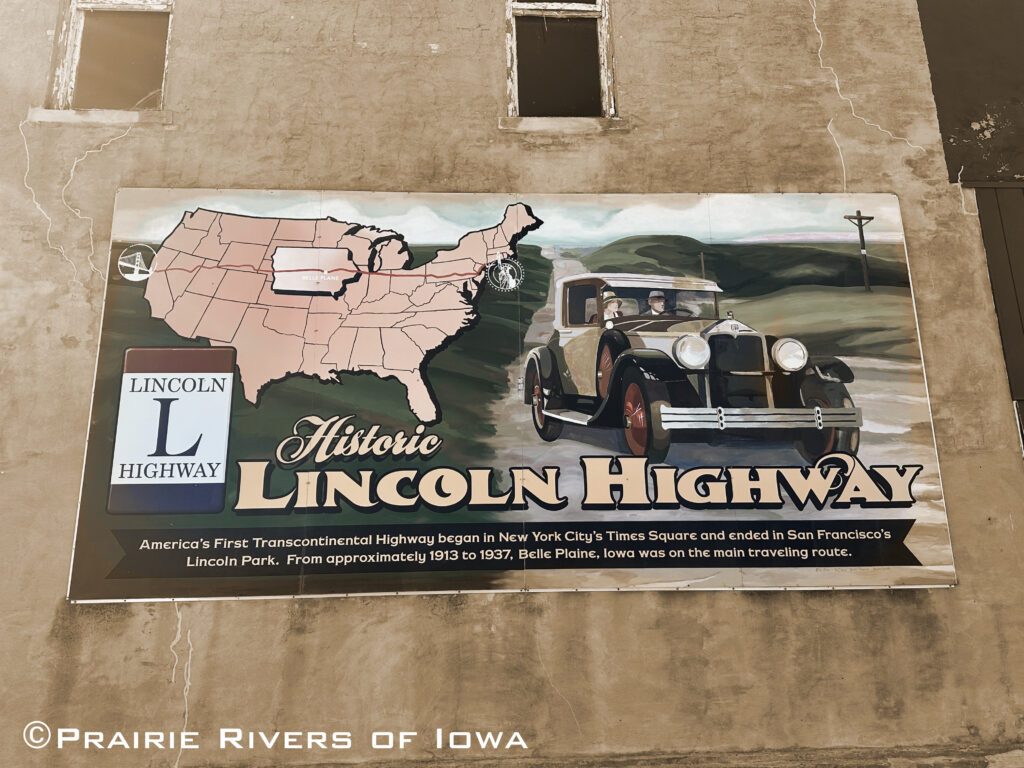

Elizabeth (Lizzie) was inspired to create this dining experience from the rich history of the town in which she lives. The Mississippi & Missouri (M & M) Railroad Co extended its rail line from Iowa City to Marengo in 1860. A short 18 months later the railroad line was continued to Wilson (present day Victor) and finally Council Bluffs. The train brought thousands of passengers and freight through the Iowa Valley including presidents Truman and Eisenhower and even the Liberty Bell. The local newspaper reported in 1899 the anticipation of an Orphan Train to arrive in Marengo; several children were received in homes in Koszta, Blairstown, South Amana, and Marengo. Although Marengo received its last passenger train in 1970 and the depot was destroyed sometime in the 1980s, a portion of the original depot from Wilson (Victor) can be seen at the Iowa County Pioneer Heritage Museum.

Lizzie’s Dining Car & Caboose Bar is not a historic train car. What is preserved at Lizzie’s is the atmosphere of a historic moment. It is an immersion of the senses into a time when the world was opened up to new possibilities through train travel.

The unique atmosphere was created within two walls of a downtown storefront. As you enter the dining car, layered drapes of vintage fabric frame windows which are actually televisions. The televisions display movement through woodlands, beaches, or winter scenes. The visual creates a sensation that you are on a moving train. On each side of the aisle are small booths igniting an intimacy for quiet conversation. Boxcar Meatloaf or Atlantic Railroad seafood and a drink from the bar completes the scene.

At the end of the railroad car is the Caboose Bar. The countertop is a single piece of cut tree that adds a natural element to the traditional “L” bar configuration found on a passenger train. The illusion is complete.

Marengo is located in the heart of the Iowa Valley Scenic Byway where a rich collection of cultures, stories, activities, and historic scenic views remain today. The preservation of our stories is only limited by the creativity used in choosing how to tell them.

Information for this article was informed by articles written by Bob James for 98.1 KHAK published May 16, 2023 and Marilyn Rodger, Guest columnist for the Southeast Iowa Union published Sep. 14, 2023 and Elizabeth Colony, owner/operator of Lizzie’s. For more information on Lizzie’s Dining Car & Caboose Bar visit Facebook.