Fall 2020 Water Quality Snapshot finds sensitive critters

Thirteen volunteers braved the cold on October 24 to test water quality in Squaw Creek, the South Skunk River, and their tributaries. For some, this was their 14th Fall Water Quality Snapshot. For others it was their first time doing stream monitoring. What we found defies easy categorization.

Update: The name “Squaw Creek” was officially changed to “Ioway Creek” in February of 2021, to be more respectful to native peoples. Over the next year, expect to see some changes to the names of the Squaw Creek Watershed Coalition and other groups that have formed to protect the creek, as well as maps and signs.

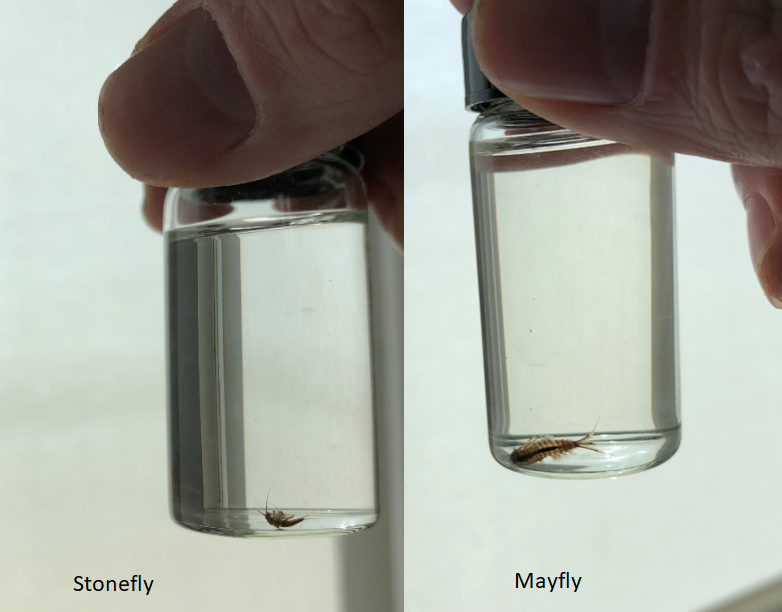

By some indicators, water quality in Squaw Creek was good. Since I wasn’t sure how many creeks would be flowing when I planned this event, I added bug collection to the agenda to keep us busy. Excuse me. Benthic macroinvertebrate sampling. We were pleased to find tiny stoneflies and mayflies. They’re good fish food, ask any fly fisherman! Excuse me. An important part of the aquatic food web. These insects also act as a sort of canary in the coal mine. They need water with a lot of dissolved oxygen so will be rare or missing in streams with too much pollution, murky water, or not much in the way of habitat.

Fun fact: while the adult mayfly is notorious for living only 24 hours, the juvenile form (naiad) lives in the stream for several years. If you’re curious what adult mayflies and stoneflies look like, I found some photos from our neighbors in Missouri.

By some indicators, water quality in Squaw Creek and it’s tributaries was bad. As in, there’s poop in the water. Excuse me, fecal indicator bacteria. This month, E. coli bacteria in Squaw Creek continued to exceed the primary contact recreation standard, and College Creek jumped above secondary contact standard. I wondered if this spike might be due to accumulated… debris… being washed out of the storm sewers and off the landscape by the 1.25 inch rain we received Thursday and Friday, but the lab samples were actually collected on Wednesday Oct 21, so I’m not sure. Anyway, covid-19 is not the only reason I bring hand sanitizer to these events!

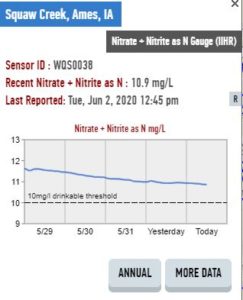

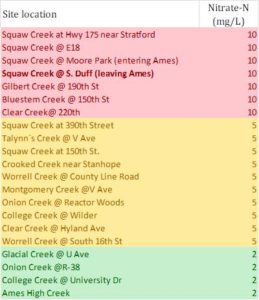

By some indicators, water quality was unusually dry this fall. Nitrate was too low to detect at 13 of 16 sites we tested. Under wetter conditions, as we had this spring or last fall, nitrate in these same streams was higher and differences due to landuse or conservation practices in the watershed become more apparent.

| Site | Watershed | Fall 2020 | Spring 2020 | Fall 2019 |

| Squaw Creek @ Duff Ave | Rural and urban | 0 | 10 | 5 |

| Bluestem Creek @150th St | Rural | 2 | 10 | 5 |

| Glacial Creek @ U Ave | Rural (with a constructed wetland) | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| College Creek @ University | Urban | 0 | 2 | 2 |

Water quality is rarely all good news or all bad news. Citizen science can us a more complete picture.

Thanks to all our intrepid volunteers!